Alaska Purchase

.jpg)

The Alaska Purchase was the purchase of Alaska by the United States from the Russian Empire in 1867. The purchase, made at the initiative of United States Secretary of State William H. Seward, gained 586,412 square miles (1,518,800 km2) of new United States territory. Originally organized as the Department of Alaska, the area was successively the District of Alaska and the Alaska Territory before becoming the modern state of Alaska upon being admitted to the United States in 1959.

Contents |

Background

Russia was in a difficult financial position and feared losing Russian America without compensation in some future conflict, especially to the British, whom they had fought in the Crimean War (1853–1856). While Alaska attracted little interest at the time, the population of nearby British Columbia started to increase rapidly a few years after hostilities ended, with a large gold rush there prompting the creation of a crown colony on the mainland. The Russians therefore started to believe that in any future conflict with Britain, their hard-to-defend region might become a prime target, and would be easily captured. Therefore Tsar Alexander II decided to sell the territory. Perhaps in hopes of starting a bidding war, both the British and the Americans were approached, however the British expressed little interest in buying Alaska. The Russians then turned their attention to the United States and in 1859 offered to sell the territory to the United States, hoping that the United States would offset the plans of Russia's greatest regional rival, Great Britain. However, no deal was brokered due to the secession of seven southern states and the eventual American Civil War.[1]

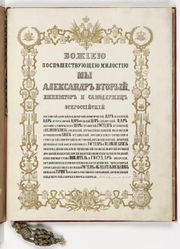

Following the Union victory in the American Civil War, the Tsar then instructed the Russian minister to the United States, Eduard de Stoeckl, to re-enter into negotiations with Seward in the beginning of March 1867. The negotiations concluded after an all-night session with the signing of the treaty at 4 o'clock in the morning of March 30, 1867,[2] with the purchase price set at $7,200,000.00 about 2.3¢ per acre ($4.74/km2).[3] American public opinion was generally positive, but some newspapers editorialized against the purchase. Horace Greeley of the New York Tribune wrote:

Already, so it was said, we were burdened with territory we had no population to fill. The Indians within the present boundaries of the republic strained our power to govern aboriginal peoples. Could it be that we would now, with open eyes, seek to add to our difficulties by increasing the number of such peoples under our national care? The purchase price was small; the annual charges for administration, civil and military, would be yet greater, and continuing. The territory included in the proposed cession was not contiguous to the national domain. It lay away at an inconvenient and a dangerous distance. The treaty had been secretly prepared, and signed and foisted upon the country at one o'clock in the morning. It was a dark deed done in the night.... The New York World said that it was a "sucked orange." It contained nothing of value but furbearing animals, and these had been hunted until they were nearly extinct. Except for the Aleutian Islands and a narrow strip of land extending along the southern coast the country would be not worth taking as a gift.... Unless gold were found in the country much time would elapse before it would be blessed with Hoe printing presses, Methodist chapels and a metropolitan police. It was "a frozen wilderness.[4]

While criticized by some at the time, the financial value of the Alaska purchase turned out to be many times greater than what the United States had paid for it. The land turned out to be rich in resources (including gold and oil) and also provided the United States a great advantage in the Cold War.

Ratification and enactment

The United States Senate ratified the treaty on April 9, 1867, by a vote of 37-2. However, the appropriation of money needed to purchase Alaska was delayed by more than a year due to opposition in the House of Representatives. The House finally approved the appropriation in July 1868, by a vote of 113-48.[5]

In 1866, the Russian government offered to sell Alaska to the United States. Russia had claimed parts of the territory since 1741, but by the mid-nineteenth century, British and American settlers were pressing Alaska's southern border, increasing the likelihood of territorial quarrels. Furthermore, the Russian treasury was short of funds. Accordingly, Baron Edouard de Stoeckl, the Russian minister to the United States, was instructed in December 1866 to negotiate the sale. He and Secretary of State William H. Seward worked out a treaty under which the United States would purchase Alaska for $7.2 million in gold. Seward initially offered $5 million, an amount Stoeckl was empowered to accept. But Stoeckl correctly judged that the secretary would agree to a higher figure because of Seward's passionate commitment to American expansion as well as his wish to conclude the matter while Congress was still in session. Stoeckl received final approval of the treaty terms from his government on March 30, 1867.

When it became clear that the Senate would not debate the treaty before its adjournment on March 30, Seward persuaded President Andrew Johnson to call the Senate back into special session the next day. Many Radical Republicans scoffed at "Seward's folly," although their criticism appears to have been based less on the merits of the purchase than on their hostility to President Johnson and to Seward as Johnson's political ally. Seward mounted a vigorous campaign, however, and with support from Charles Sumner, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, won approval of the treaty on April 9 by a vote of 37-2.

For more than a year, as congressional relations with President Johnson worsened, the House refused to appropriate the necessary funds. But in June 1868, after Johnson's impeachment trial was over, Stoeckl and Seward revived the campaign for the Alaska purchase. Combining public appeals and private persuasion (including bribes to a number of key Republicans), they won a favorable vote on July 14. With the purchase of Alaska, the United States acquired an area twice as large as Texas, but it was not until the great Klondike gold strike in 1896 that Alaska came to be seen generally as a valuable addition to American territory.

Sumner reported Russian estimates that Alaska contained about 2,500 Russians and those of mixed race, and 8,000 Indigenous people, in all about 10,000 people under the direct government of the Russian fur company, and possibly 50,000 Inuits and Alaska Natives living outside its jurisdiction. The Russians were settled at 23 trading posts, placed conveniently on the islands and coasts. At smaller stations only four or five Russians were stationed to collect furs from the natives for storage and shipment when the company's boats arrived to take it away. There were two larger towns. New Archangel, now named Sitka, had been established in 1804 to handle the valuable trade in the skins of the sea otter and in 1867 contained 116 small log cabins with 968 residents. St. Paul in the Pribilof Islands had 100 homes and 283 people and was the center of the fur seal industry.

An Aleut name, "Alaska," was chosen by the Americans. The transfer ceremony took place in Sitka on October 18, 1867. Russian and American soldiers paraded in front of the governor's house; the Russian flag was lowered and the American flag raised amid peals of artillery. Captain Alexis Pestchouroff said, "General Rousseau, by authority from His Majesty, the Emperor of Russia, I transfer to the United States the territory of Alaska." General Lovell Rousseau accepted the territory. A number of forts, blockhouses and timber buildings were made over to the Americans. The troops occupied the barracks; General Jefferson C. Davis established his residence in the governor's house, and most of the Russian citizens went home, leaving a few traders and priests who chose to remain.

Alaska Day celebrates the formal transfer of Alaska from Russia to the United States, which took place on October 18, 1867. October 18, 1867, was by the Gregorian calendar and a clock time 9:01:20 behind Greenwich, which came into effect the following day in Alaska to replace the Julian calendar and a clock time 14:58:40 ahead of Greenwich. For the Russians, the handover was on October 7, 1867.

See also

- Adams-Onís Treaty

- Louisiana Purchase

Notes

- ↑ "Purchase of Alaska, 1867". Archived from the original on 2008-04-10. http://web.archive.org/web/20080410122537/http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ho/time/gp/17662.htm.

- ↑ Seward, Frederick W., Seward at Washington as Senator and Secretary of State. Volume: 3, 1891, p. 348

- ↑ A simple consumer price index calculation would put this at the equivalent of around one hundred million dollars in 2007; however, given the scale of the project, it would be more appropriate to consider the cost as a fraction of the national wealth, in which case it would be the equivalent of around eleven billion dollars today. Considered as a fraction of government expenditure, it would be even larger; the federal government in 1867 had a far smaller budget as a proportion of GDP than it does today, and so the Alaska Purchase represented a more significant investment to the government than the figure of eleven billion dollars would suggest. For calculations, see "Six Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a U.S. Dollar Amount", Samuel Williamson, 2008.

- ↑ Oberholtzer, Ellis Paxson. A History of the United States since the Civil War. Volume: 1. 1917. p. 123

- ↑ "Treaty with Russia for the Purchase of Alaska: Primary Documents of American History (Virtual Programs & Services, Library of Congress)". Loc.gov. http://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/ourdocs/Alaska.html. Retrieved 2008-09-15.

References

- Jensen, Ronald (1975). The Alaska Purchase and Russian-American Relations.

- Oberholtzer, Ellis (1917). A History of the United States since the Civil War. vol 1.

- Alaska. Speech of William H. Seward at Sitka, August 12, 1869 (1869; Digitized page images & text), primary source.

External links

- Treaty with Russia for the Purchase of Alaska and related resources at the Library of Congress

- Text of Treaty with Russia

- Meeting of Frontiers, Library of Congress

- Original Document of Check to Purchase Alaska

- US Government article

- Britannica article

|

||||||||

|

|||||||